- Published on

Understanding Currying in JavaScript with an Example

- Authors

- Name

- Ashutosh

- @bhardwajashu96

Overview

The functional programming paradigm has been gaining traction in the JavaScript community for quite some time. It’s hard to pinpoint when it all started, but I believe with the introduction of features like arrow functions, map, filter, reduce, etc., in ES6 (2015), we’re seeing a lot more functional programming code in JavaScript. Therefore, it would be fair to say one might expect functional programming questions in a JavaScript interview. For instance, let’s take a look at the following problem statement:

For example:

add3(1, 2, 3) // 6

add3(1)(2, 3) // 6

add3(1)(2)(3) // 6The function invocation looks strange, to say the least. No worries, in this article, we will learn how to implement such a function using functional programming concepts. So without further ado, let’s begin.

Basics

If we think about the add3 function, among other things, it should somehow partially apply the arguments passed to it.

In other words, it should apply them one at a time.

In functional programming, there is a concept known as currying.

We will use this same concept to our aid while implementing the add3 function. Let’s see how:

Foundation

/**

* The underlying base function is "add" which takes 3 arguments and return their sum.

*/

const add = (a, b, c) => a + b + c

/**

* We need such a function which will transform the base function such that

* it can also process its argument one by one.

*/

const curry = (baseFunc) => {

// TODO: Do something with it.

}

const add3 = curry(add)All the code examples are in Code Sandbox and here is the CodeSandbox link to the final output. Let’s get started.

Base Case

In its simplest form, the add3 function is equivalent to base function(add). In other words, the curry function will return the original function passed to it as an argument. With that in mind, let’s start the implementation:

/**

* The underlying base function is "add" which takes 3 arguments and return their sum.

*/

const add = (a, b, c) => a + b + c

/**

* We need such a function which will transform the base function such that

* it can also process its argument one by one.

*/

const curry =

(baseFunc) =>

(...args) =>

args.length === baseFunc.length ? baseFunc(...args) : curry(baseFunc)

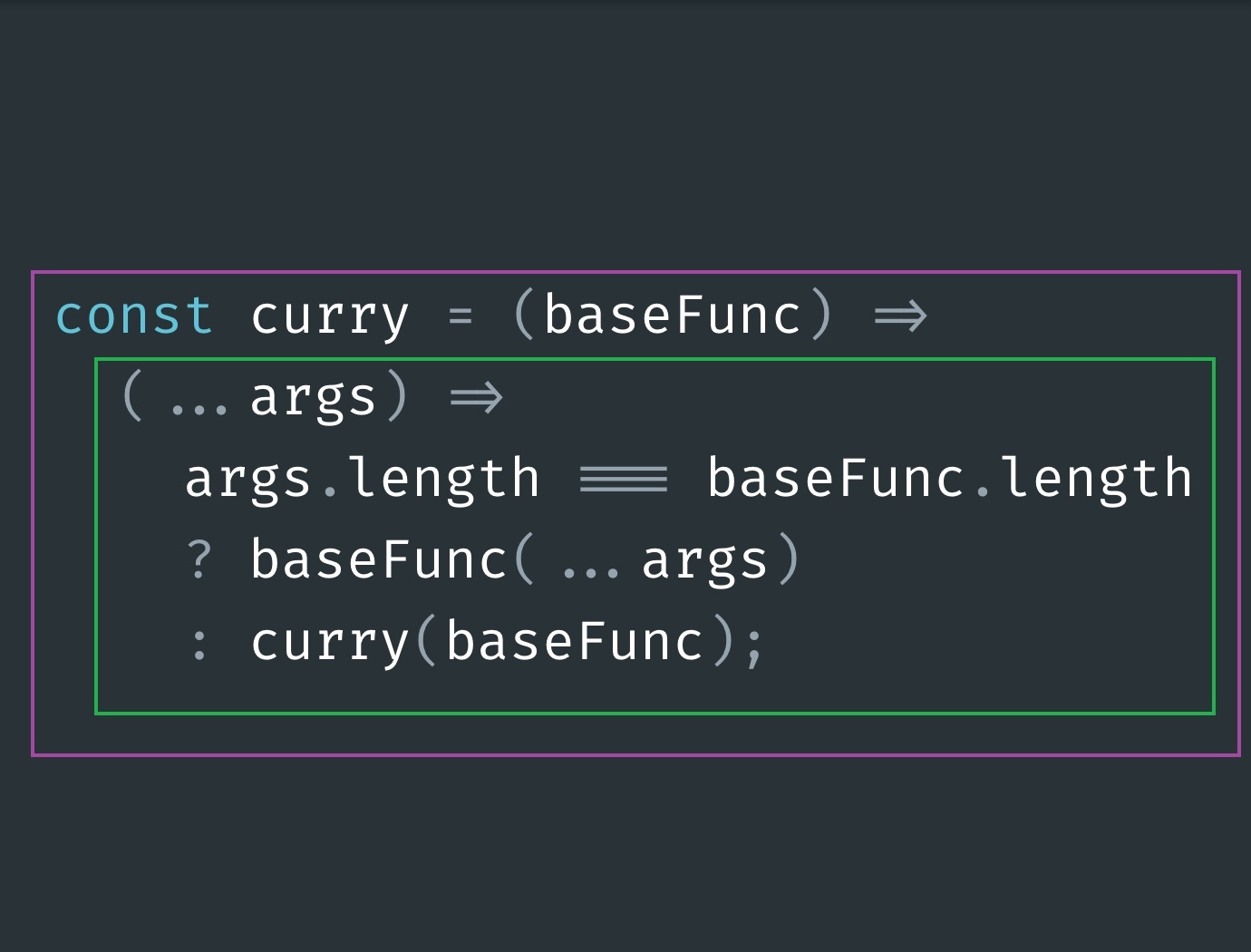

const add3 = curry(add)Let’s decode the function implementation:

Curry is a function (highlighted by the purple rectangle) that returns an anonymous function(highlighted by the green rectangle). The inner function do the following:

- aggregate all of the arguments into a single parameter named args using the rest parameter

- then check whether the arguments passed to it has the same length as the base function(

baseFunc) arguments - if that is the case, we execute the base function with the provided arguments spread using the spread operator

- otherwise, we need to carry on the process somehow, but more on that later

Now, let’s understand what happens when we execute the following line of code:

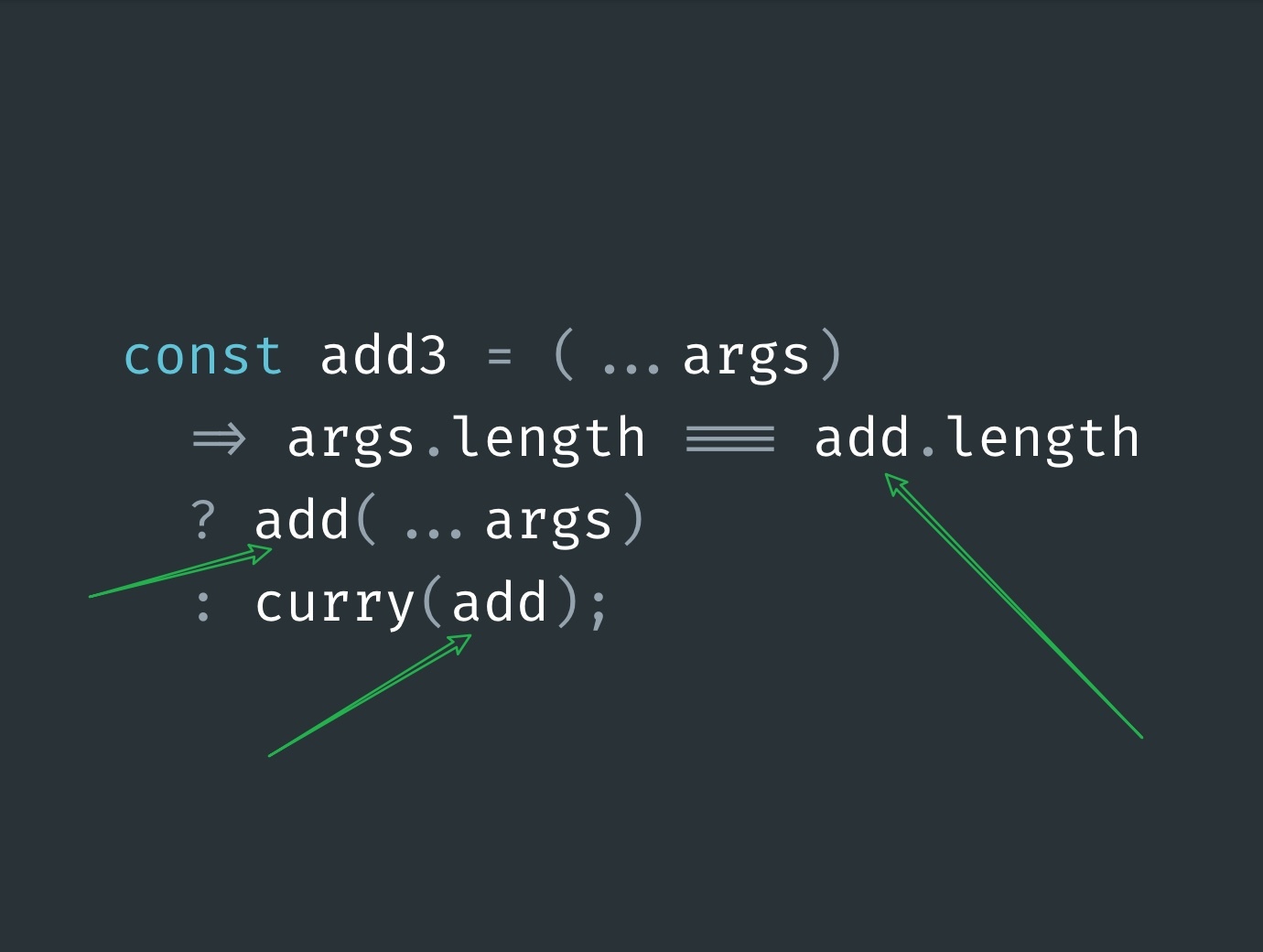

const add3 = curry(add)The add3 gets assigned the function returned by the curry function with baseFunc param gets replaced by the argument value that is add:

Now, let’s understand how the following line of code gets evaluated to 6:

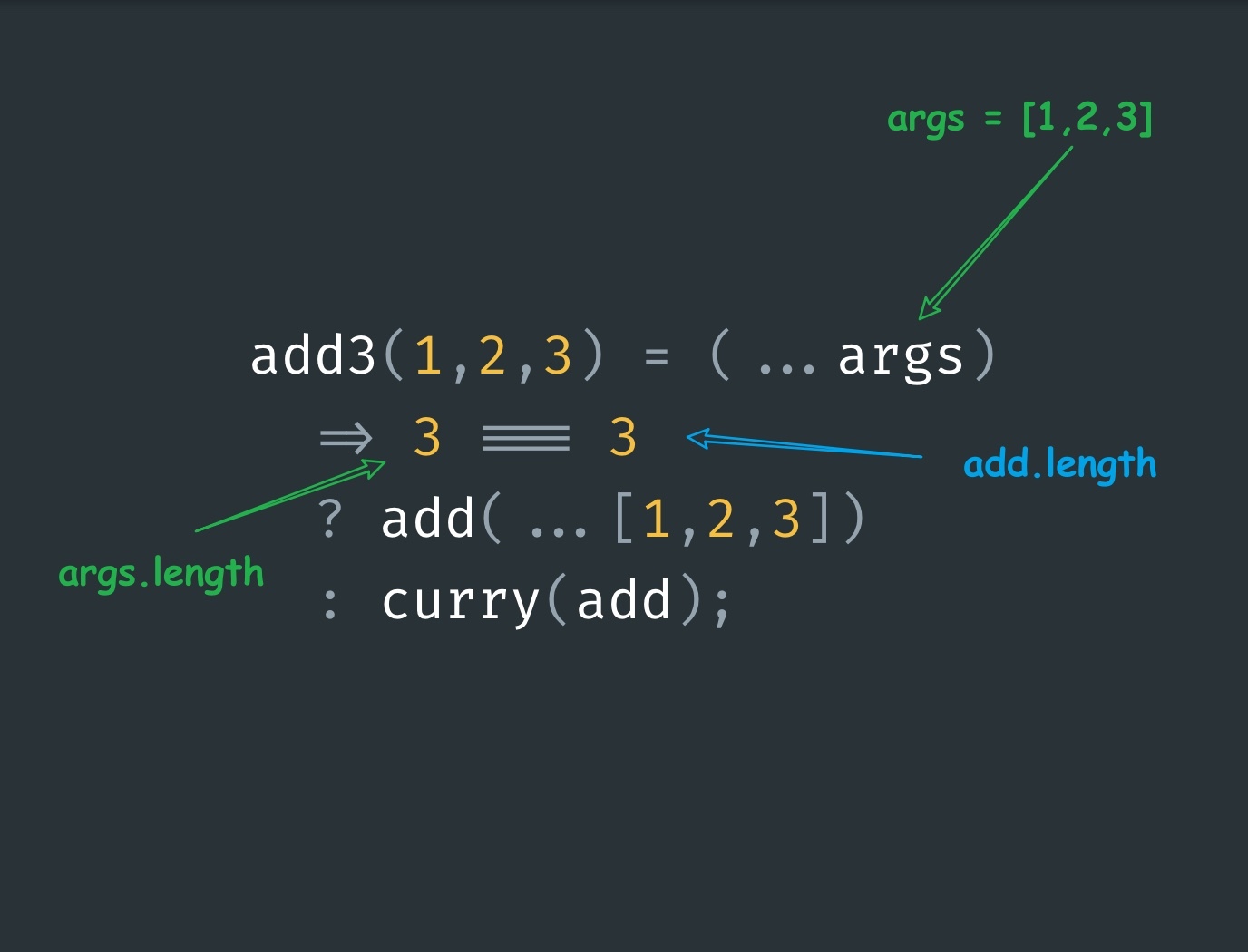

add3(1, 2, 3)Execution illustration:

When we call the add3 function with arguments 1, 2, 3. They get aggregated into a single parameter named args as an array. Therefore, we’re able to calculate the argument length which is 3 in this case.

We know it’s our base case because args.length is equal to add.length therefore we return the result of add function by passing along the arguments.

Note: We do spread the arguments before passing because the underlying base function expects them individually rather than an array.

So far so good. Now, let’s figure out how to make our curry function work for the following use cases:

- add(1)(2, 3) // 6

- add(1)(2)(3) // 6

Recursive Case

If we were to call, add3 as add(1)(2,3) using our current implementation, it would stop the execution just after the first call add(1).

To handle these cases, we need to add the following ability to the curry function:

- accumulating the arguments over time (partially applying the arguments)

- chaining execution (with the help self-invoking function)

Let’s see how we can achieve the desired result by rewriting the curry function.

/**

* The underlying base function is "add" which takes 3 arguments and return their sum.

*/

const add = (a, b, c) => a + b + c

/**

* We need such a function which will transform the base function such that

* it can also process its argument one by one.

*/

const curry =

(baseFunc, accumlatedArgs = []) =>

(...args) =>

((a) => (a.length === baseFunc.length ? baseFunc(...a) : curry(baseFunc, a)))([

...accumlatedArgs,

...args,

])

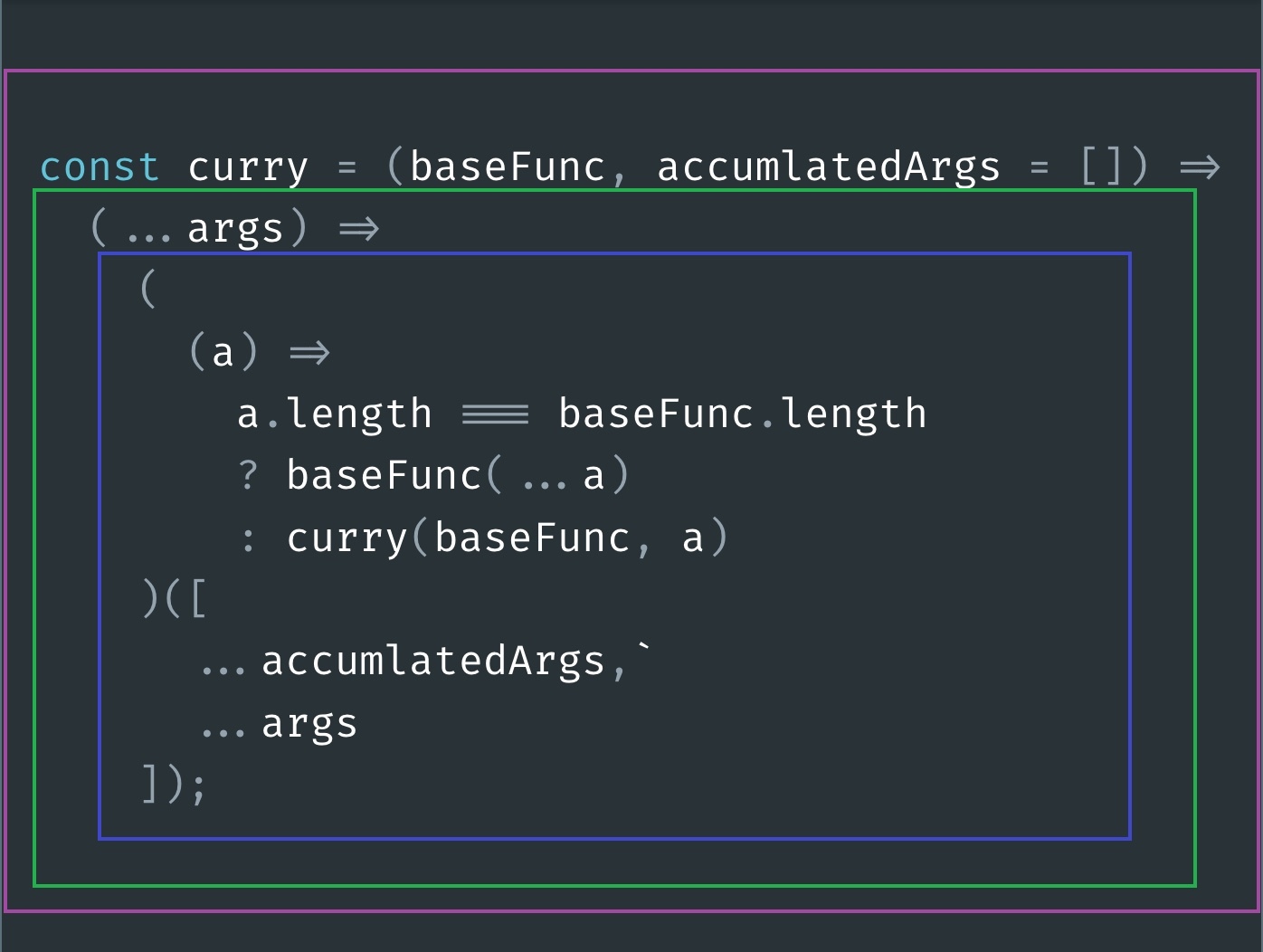

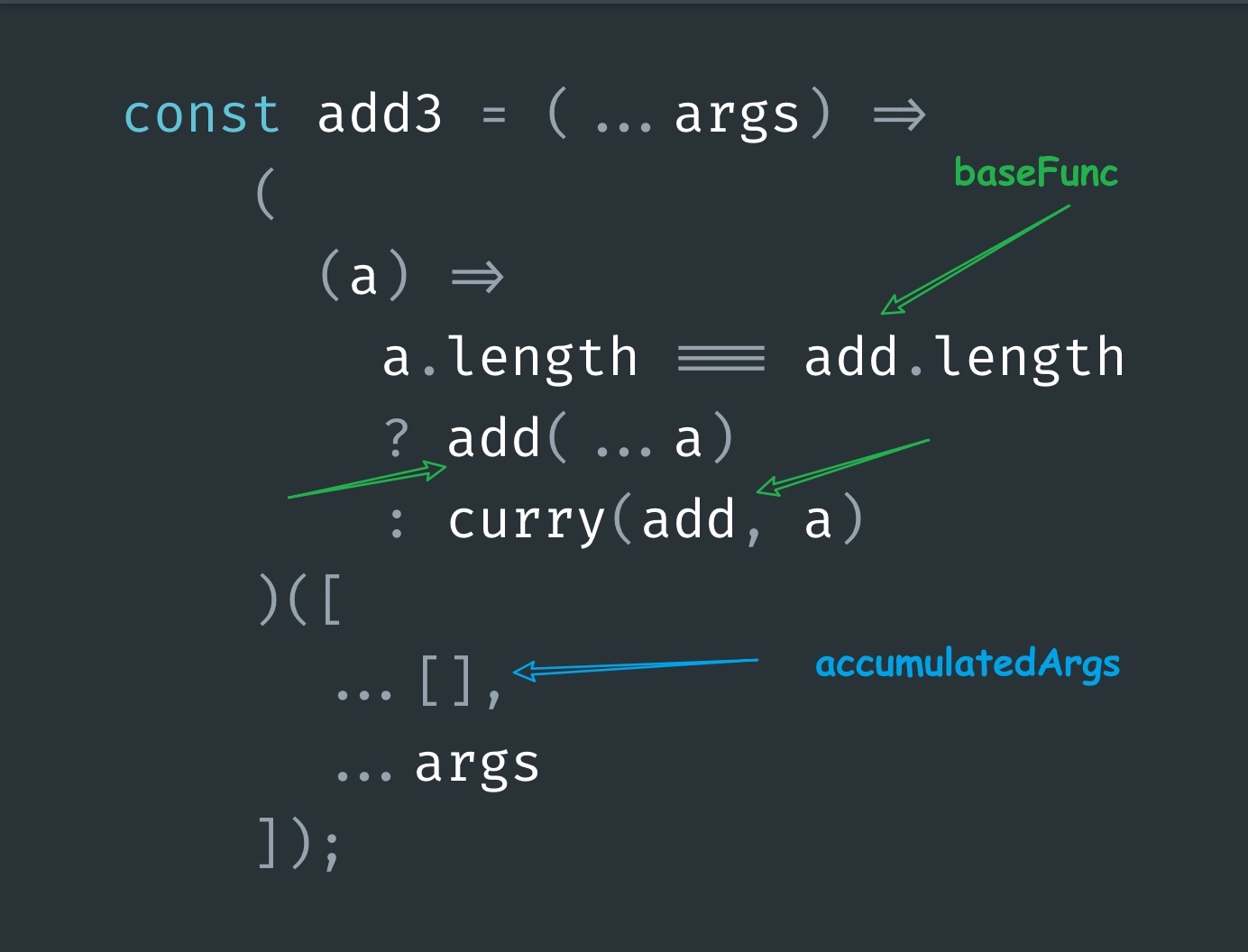

const add3 = curry(add)Let’s not get ahead of ourselves and understand the updated curry function:

Curry is a function (highlighted in a purple rectangle) that returns an anonymous function(highlighted in a green rectangle) that returns another anonymous function(highlighted in a blue rectangle) that does

the same thing that the green function did previously. But there are two things in this case.

- First, the curry function takes a second parameter named

accumlatedArgswhich is assigned an empty array as the default argument value. - Second, the innermost function(blue) is an Immediately Invoked Function Expression better known as IFFE and we’re passing an array to it which contains all the accumulated arguments as well as the current arguments.

Now, let’s understand what happens when we execute the following line of code:

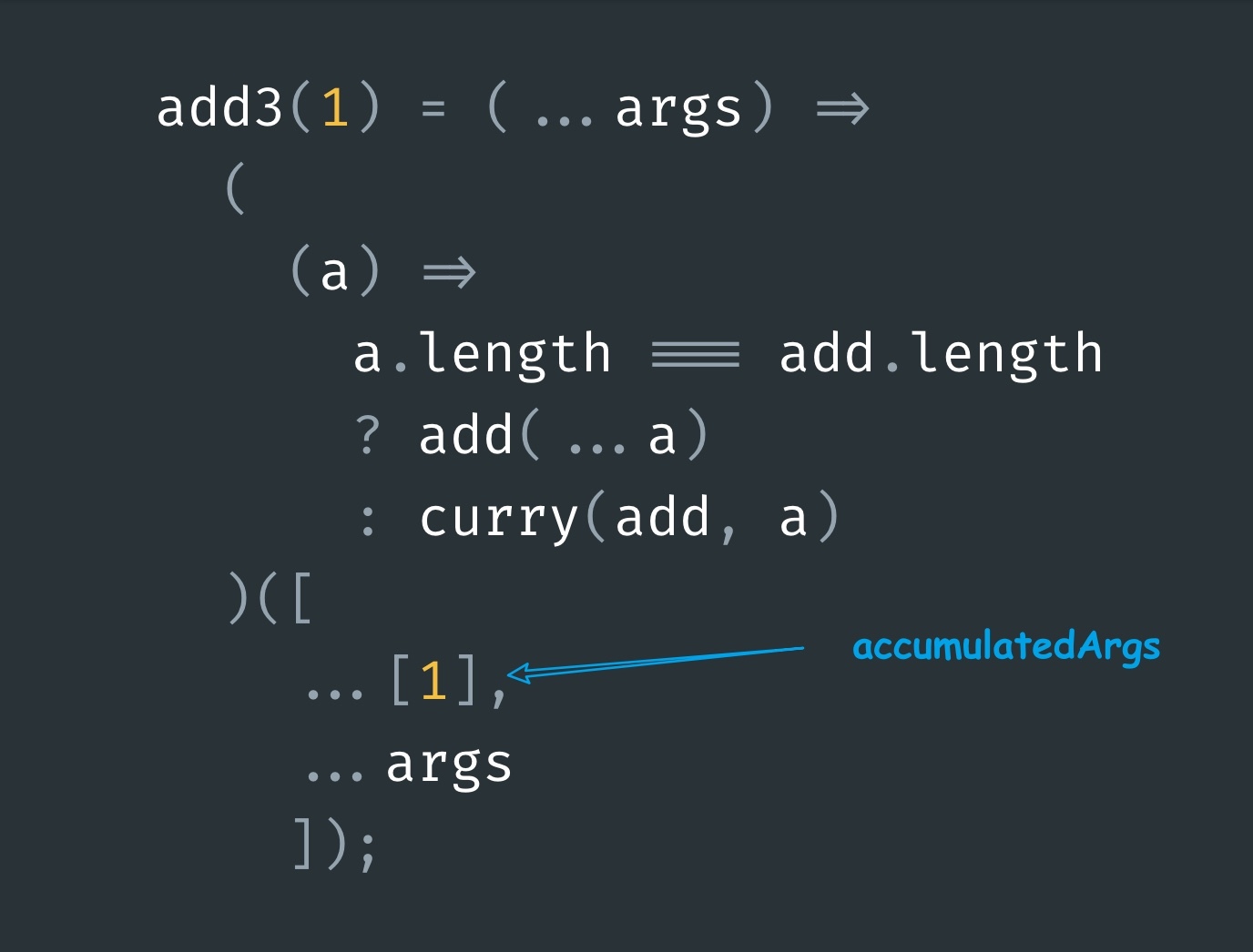

const add3 = curry(add)add3 gets evaluated as the following:

Notice that because we didn’t pass any argument value for accumulatedArgs param, the default param value gets assigned here.

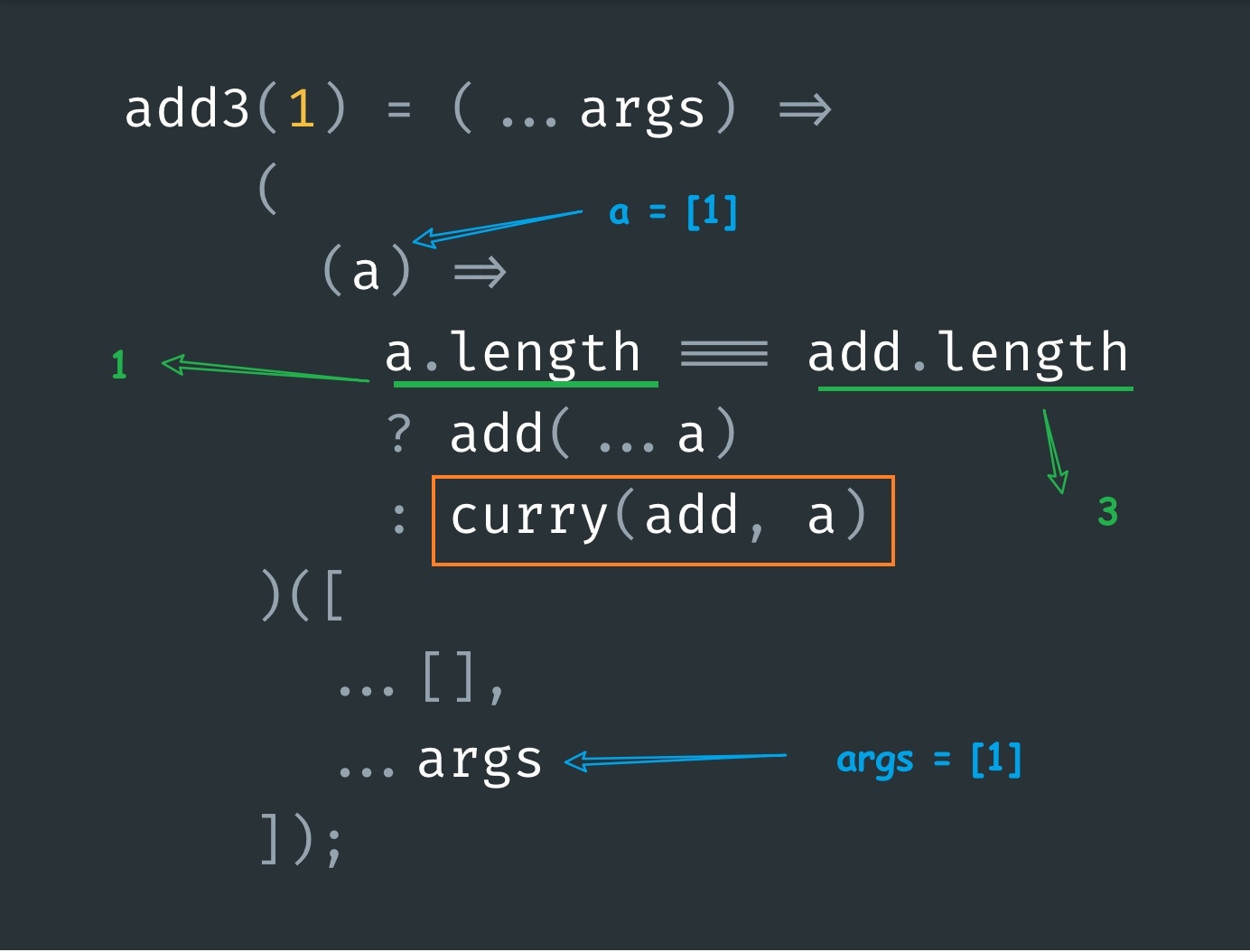

Let’s take a walkthrough of the execution of add3(1).

Because accumulatedArgs is an empty array([]) and args is [1] the param a becomes equal to [1] which means the ternary operator condition results in false and we get:

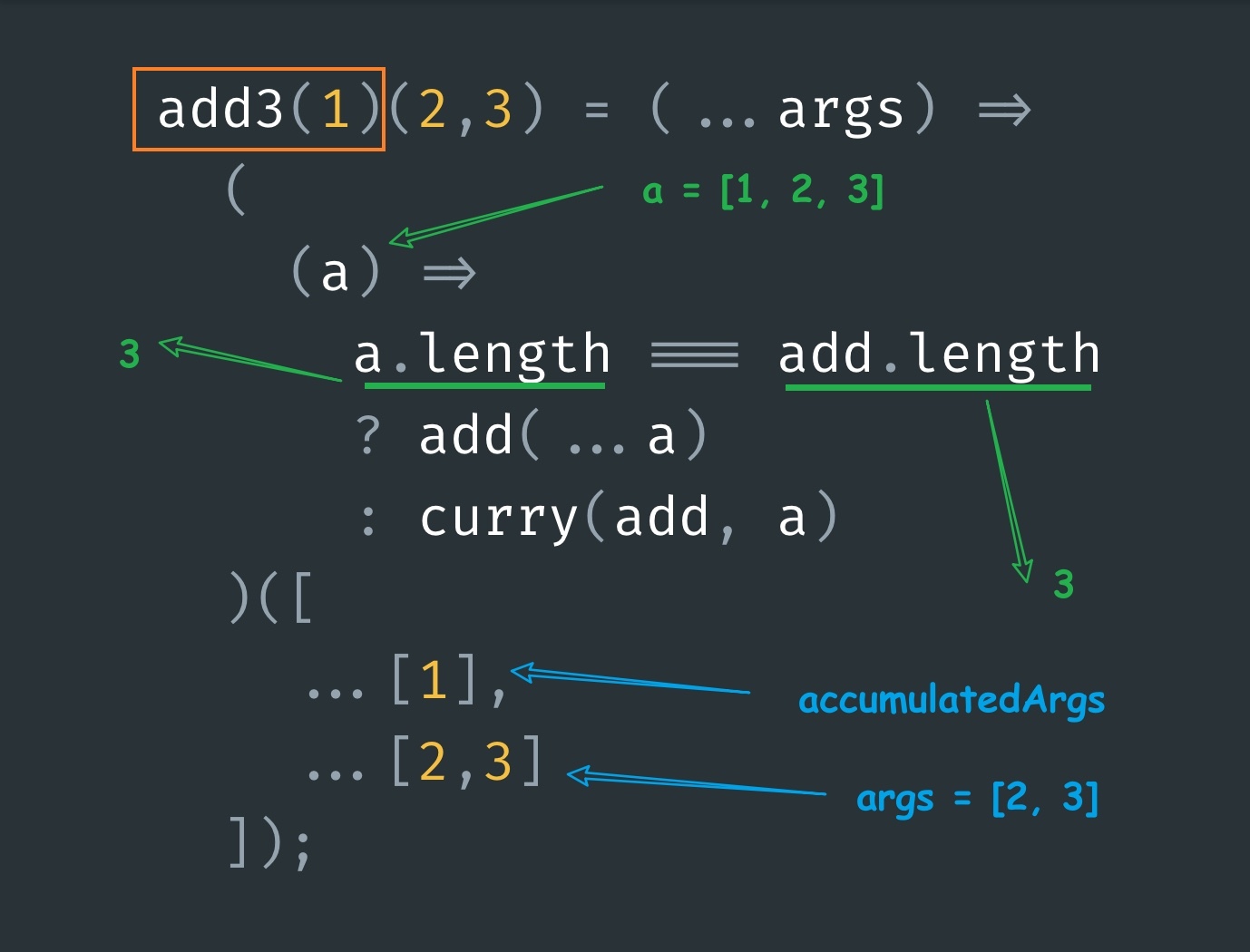

add3(1) = curry(add, [1])Now, let’s see the execution of add3(1)(2,3):

This time accumulatedArgs is [1] and args is [2,3] so the param a becomes equal to [1,2,3] which means this time the ternary condition results in true and we call the base function with a:

which is basically the base case. Logically, it’s equal to:

add3(1)(2,3) = add(1,2,3) = 6Notice, how we accumulated the arguments that was passed into the add3 function.

Final Case

Now, let’s also do the final case which is

add3(1)(2)(3)but this time we use logs in our code to see how the execution is taking place:

const add = (a, b, c) => a + b + c

const curry =

(baseFunc, accumlatedArgs = []) =>

(...args) =>

((a) => {

console.log('Received => ', JSON.stringify({ accumlatedArgs, args, a }))

return a.length === baseFunc.length ? baseFunc(...a) : curry(baseFunc, a)

})([...accumlatedArgs, ...args])

const add3 = curry(add)

console.log('add3(1)(2)(3) => ', add3(1)(2)(3))And as we expect, it accumulates the arguments provided to it over a while in sequential invocation. We get the following output:

Received => {"accumlatedArgs":[],"args":[1],"a":[1]}

Received => {"accumlatedArgs":[1],"args":[2],"a":[1,2]}

Received => {"accumlatedArgs":[1,2],"args":[3],"a":[1,2,3]}

add3(1)(2)(3) => 6

Conclusion

As you can see, we have successfully built the solution from the ground up using first principles. The example mentioned in the article is rather straightforward but in real-world scenarios, you will encounter other use cases for currying techniques in JavaScript. And, now, you can apply the same approach to build such a solution :)

I hope you find this article interesting and helpful. If you did, please give it a like and share it with someone who might benefit from it.

My name is Ashutosh, and apart from working as a Full-stack engineer, I love to share my learnings with the community. You can connect with me on LinkedIn and follow me on Twitter.

If you prefer video format please do check out my YouTube video: